Interrupting Intergenerational Trauma: Addressing American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Youth Houselessness in Los Angeles County

May 8, 2023

Dear Ms. Karen Bass,

Attached is a report entitled “Interrupting Intergenerational Trauma: Addressing American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Youth Houselessness in Los Angeles County.” It provides crucial background information, policy alternatives, and a final recommendation regarding houselessness among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth ages 13-17 in Los Angeles County — primarily from the Tongva, Tataviam, Serrano, Kizh, and Chumash Tribes.

A long history of colonization, displacement, and forced assimilation has caused intergenerational trauma and exacerbated houselessness risk factors among American Indian and Alaska Native youth. In order to address these issues, however, we need to have a better fundamental understanding of this subpopulation. As such, this report recommends launching a bi-annual questionnaire to collect accurate data and information about AI/AN youth.

The time to act is now. For too long, Los Angeles County has refused to remedy the harms committed against American Indian and Alaska Native communities and their youth. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Sincerely,

Nikki Ramsy

Executive Summary

The rate of houselessness among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth is three times that of the national average. Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, they face higher rates of poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, mental and physical health issues, and high school absenteeism and incompletion — which are all risk factors for houselessness. Historical and ongoing colonization, displacement, and forced assimilation of American Indian and Alaska Native peoples has created a cycle of intergenerational trauma and perpetuated the aforementioned issues.

This paper discusses three main policy alternatives: data collection campaign, Tongva land transfers, and property tax reallocation. The final recommendation is the data collection campaign due to its high political feasibility and wide potential impact. It will be one step closer to filling the gaping data gap and lack of information regarding American Indian and Alaska Native populations.

Background

The term “American Indian and Alaska Native,” or “AI/AN,” refers to an individual belonging to an indigenous tribe in what is now known as the United States. Throughout this paper, I will also use “unhoused” or “houselessness” instead of “homelessness” or “homelessness” in order to emphasize that many individuals who do not have stable physical shelter feel as though they have a home and established community.

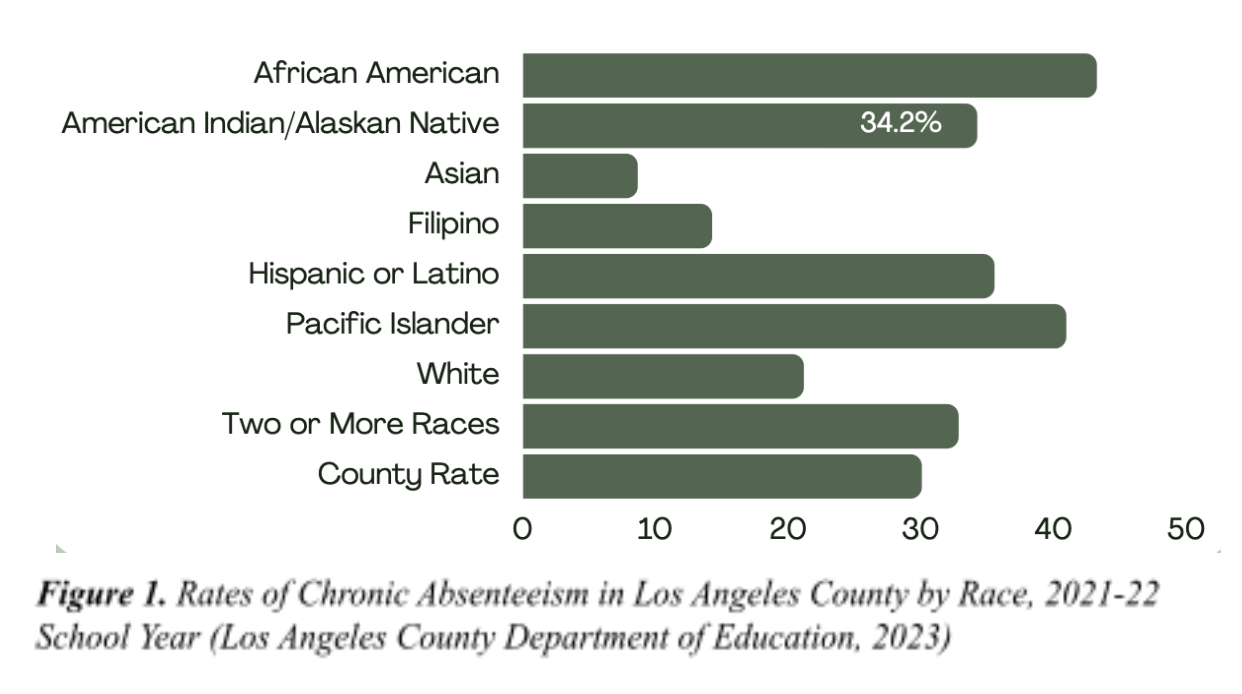

In the United States, one in 30 youth ages 13-17 are unhoused (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023). Among AI/AN youth specifically, however, this rate triples to one in 10 (Morton et al., 2019). Concurrent — and interrelated — with this high rate of houselessness amongst AI/AN youth is poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, poor mental and physical health, and school absenteeism and incompletion. 33 percent of AI/AN children under the age of 18 live in poverty compared to the national average of 18 percent (National Congress of American Indians, 2022). As one can see in

Figure 1, AI/AN chronic absenteeism is 34 percent, second only to African American students. In 2018, the AI/AN high school graduation rate was 74 percent, the lowest of any other racial/ethnic group (Cai, 2020).AI/AN children and adolescents also have the highest rates of lifetime major depressive episodes (American Psychiatric Association, 2017) and suicide (Scott et al., 2016). AI/AN youth ages 12-17 also have one of the highest rates of illicit drug use and heavy drinking (Dickerson et al., 2016). Obesity for AI/AN adolescents is 34 percent, substantially higher than the United States average of 20 percent, leading to greater risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (Johnson-Jennings et al., 2023).

These issues, of course, do not exist in a vacuum. Colonization has displaced American Indian and Alaska Native people from their lands since Europeans settled in the fifteenth century (Library of Congress, n.d.). During the Reservation Era from 1850 to 1887, the federal government restricted native peoples to the least arable tracts of land, stripping them of their autonomy and assimilating them into mainstream cultural practices (Digital Public Library of American, n.d.). In 1956, the Indian Relocation Act moved many American Indians and Alaska Natives to urban areas such as Chicago, Houston, New York, and Denver — leaving them unhoused, unemployed, and separated from their communities (Dickerson et al., 2016).

Such historical events have led to deep intergenerational trauma in AI/AN communities. As scholars Myrha and Wieling write:

For AI/AN people, historical trauma refers to the generational suffering of genocide and ethnocide resulting from broken treaties and damaging government policies aimed at assimilation and extinction. (Myrha & Wieling, 2014)

This intergenerational trauma can cause and compound the main risk factors of houselessness: physical and emotional abuse, mental health issues, suicidality, and drug use (Nilsson et al., 2019).

Los Angeles County Natives

An estimated 168,537 American Indian and Alaskan Native people live in Los Angeles County (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). It is home to the Tongva, Tataviam, Serrano, Kizh, and Chumash Peoples (County of Los Angeles, n.d.). In 1851 and 1852, the U.S. Government Treaty Commissioners signed 18 treaties with various indigenous communities across California allocating 8.5 million acres for Indian reservations. But due to pressure from white Californians who wanted the land, the U.S. Senate never ratified the treaties and they became known as the “18 lost treaties” (Dobson & Nez, 2023; Miller, 2013). Although there are now nearly 100 reservations throughout California (Judicial Council of California, n.d), the legacy of the “18 lost treaties” remain and there are no reservations in Los Angeles County.

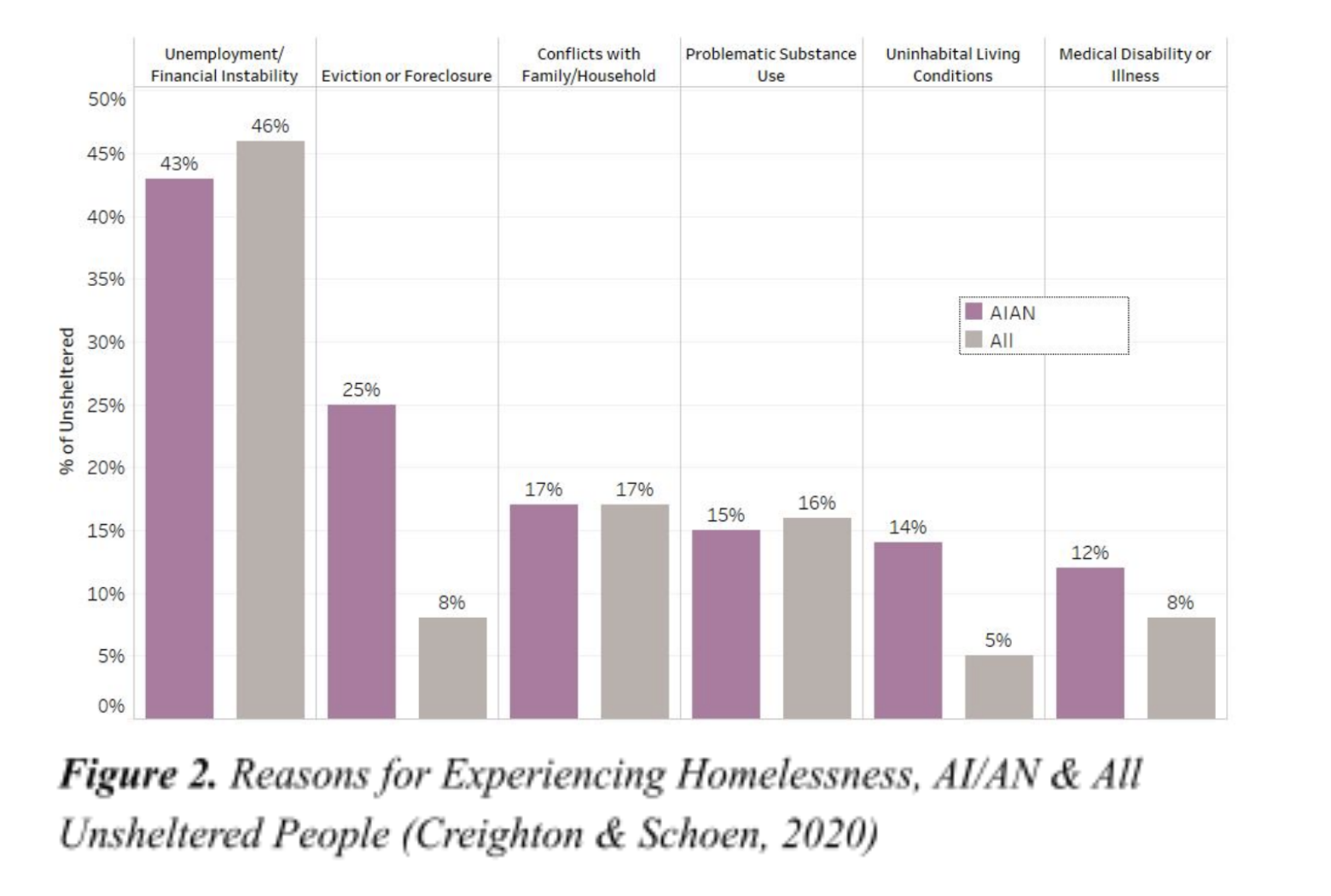

In a 2016 survey administered to the Los Angeles County AI/AN population by Healthy LA Natives, 14 percent of respondents reported experiencing houselessness (Creighton & Schoen, 2020). As one can see in Figure 2, a 2019 Homeless Count conducted by the Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority, unhoused AI/AN people cited six main reasons for experiencing homelessness: unemployment/financial instability (43 percent), eviction or foreclosure (25 percent), conflicts with family/household (17 percent), problematic substance use (15 percent), uninhabitable living conditions (14 percent), and medical disability or illness (12 percent) (Creighton & Schoen, 2020). AI/AN individuals also

xperienced chronic homelessness at a higher rate than the general population — 27 percent compared to 22 percent. Moreover, unsheltered AI/AN reported higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and severe depression than the general unsheltered population.

It is especially worth noting that 23 percent of unhoused AI/AN adults were former foster youth (compared to 13 percent of the general unhoused population). Such data highlights how crucial addressing AI/AN youth houselessness is to addressing adult AI/AN houselessness — and remedying systemic inequity at large.

Landscape Analysis

In May 2022, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority released a report entitled “Los Angeles Coordinated Community Plan to Prevent and End Youth and Young Adult Homelessness.” In it, researchers cite various programs that aim to curb youth and young adult (YYA) houselessness:

Los Angeles Regional Initiative for Social Enterprise (LA:RISE). LA:RISE, a program of Los Angeles County’s Workforce Development, Aging & Community Services Department helps youth who have been houseless or incarcerated find employment.

Department of Mental Health (DMH) Programs. DMH programs support Seriously Emotionally Disturbed and Severe and Persistently Mentally Ill transition-age-youth (ages 16-25) who are often houseless or at risk of becoming houseless.

Los Angeles County Office of Education and Los Angeles Unified School District Education Coordinators. Coordinators, who have Master’s degrees in education, social services, and other relevant fields, act as liaisons connecting unhoused YYA to LA County’s school districts.

Although these efforts are crucial and often life-saving for at-risk youth, they are not enough. Firstly, these interventions are mainly for individuals categorized as “young adults,” who are 17 and older. For children and adolescents ages 13-17, however, there are few resources and services available. In addition, virtually none of these programs are specific to AI/AN youth. As such, they lack the focused lens and cultural relevance necessary to address the issues unique to this subpopulation.

The following list, while not comprehensive, enumerates and briefly explains organizations that provide social services to American Indians and Alaska Natives in Los Angeles County:

American Indian Community Council (AICC). According to their website, AICC aims to “promot[e] and suppor[t] health and wellness” within the AI/AN Los Angeles County community (American Indian Community Council, 2020).

Pukuu Cultural Community Services. Led by the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, this organization seeks to invest in and improve culturally sensitive programs and services for AI/AN in Los Angeles County (Pukuu Cultural Community Services, 2023).

United American Indian Involvement. This organization provides services for AI/AN of all ages to “promote and support the[ir] physical, behavioral, and spiritual well-being” (United American Indian Involvement, 2020).

First Nations Development Institute. First Nations, which has an office in Claremont, California, leads various programs dedicated to native youth such as the Native Youth and Culture Fund and the Advancing Youth Development in Indian Country project (First Nations Development Institute, 2023).

Once again, with the exception of the First Nations Development Institute programs, lack of specificity remains. Although these organizations do great work for the health and well-being of AI/AN in Los Angeles, they do not have initiatives for the subpopulation of unhoused youth.

There are also various governmental entities dedicated to improving the lives of AI/AN communities in California. On a county level, the Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission, established in 1976, “increase[s] the acquisition and application of funding resources to the socioeconomic problems of American Indians in Los Angeles City and County” (Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission, n.d.). On a statewide level, the Governor’s Office of Tribal Affairs consults with California tribes about relevant policies (Governor’s Office of Tribal Affairs, 2023). The following are bills the California State Legislature passed to improve outcomes for native youth:

Assembly Bill 873. Authored by 40th District Assemblymember James Ramos, AB 873 made it easier for tribal communities to access child welfare services (California Tribal Families Coalition, 2021).

Assembly Bill 1055. Authored by James Ramos and 37th District Assemblymember Steve Bennett, AB 1055 enabled AI/AN foster youth to have the same educational rights as other foster youth (James C. Ramos, 2021).

Senate Bill 918. Authored by 11th District State Senator Scott Wiener, SB 918 created the Office of Homeless Youth to set goals and a game plan to end youth houselessness in California (California Coalition for Youth, 2018).

Problem Statement

To put in plainly, we are experiencing a youth houselessness crisis in Los Angeles County. What’s more, this issue disproportionately affects American Indian and Alaska Native youth, who experience houselessness at a rate three times the national average. It is relatively well-documented that this demographic has high rates of poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, school incompletion and absenteeism, mental health issues, and physical ailments — all risk factors for houselessness. However, research on AI/AN youth, especially those who are unhoused, is still extremely scarce (D’Amico et al., 2019; Walls et al., 2019). As such, legislation, resources, and advocacy for this subpopulation is severely lacking.

In Los Angeles, the indigenous population is urbanized. These circumstances come with unique challenges; without any designated reservation land or localized centers, it is difficult to stay connected to one’s tribal culture and community. As the Indian Health Service notes, “urban Indian youth are at greater risk for serious mental health and substance abuse problems, suicide, increased gang activity, teen pregnancy, abuse, and neglect” (Urban Indian Health Program, 2018).

There are multiple stakeholders involved in this issue. First and foremost, the AI/AN youth who are experiencing houselessness should be front and center in developing and implementing solutions. Additionally, the official Los Angeles County tribal entities are the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, Gabrieleno/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, Gabrielino Tongva Indians of California, Tribal Council San Fernando Band of Mission Indians, and San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

Governmental organizations such as the Governor’s Office of Tribal Affairs and Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission will also be closely involved. Non-government-affiliated organizations such as the American Indian Community Council, Pukuu Cultural Community Services, United American Indian Involvement, and First Nations Development Institute may also play a role in carrying out policy solutions.

Finally, non-native members of Los Angeles County must be aware of their residence on indigenous land and playing a part in mitigating — and ultimately eliminating — AI/AN youth houselessness.

Policy Alternatives

This paper recommends three policy alternatives:

Launch a data collection campaign to increase accuracy of census and demographic information regarding AI/AN youth in Los Angeles County.

Support and expedite Tongva land transfers with Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy.

Share a percentage of Los Angeles County property taxes with local tribal governments

for cultural engagement and healing efforts.

Data Collection Campaign

One of the main issues in the AI/AN Los Angeles community — and throughout the whole country — is the glaring lack of accurate data. Governmental entities inconsistently classify AI/AN and often omit large sects of the population altogether (Urban Indian Health Institute, 2020). Undercounting leads to underfunding, which perpetuates many of the issues unhoused AI/AN youth face. As such, this paper recommends working with trusted community members, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, and the Los Angeles Unified School District to administer a point-in-time (PIT) questionnaire (Bardon, 2023).

As per the Urban Institute of Health’s guidelines, AI/AN youth will be designated as AI/AN alone in (disaggregated from other racial/ethnic identifications) and will be asked their tribal affiliations. The questionnaire will survey AI/AN youth ages 13-17 in the Los Angeles County area and will be administered bi-annually during the school year and summer break (Bardon, 2023).

The calculated cost of such a data collection campaign is $1.28 million. Given that the 2020 U.S. Census cost $14.2 billion (Jones & Marinos, 2021) and counted 331,449,281 individuals (Epstein & Lofquist, 2021), the cost was $42.84 per person. This paper uses this per person estimate to generate the total cost prediction of $1.28 million. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are 29,831 AI/AN people ages 5-17 in Los Angeles County. Although this data covers a wider age range, many AI/AN are undercounted and 29,831 may be a reasonable estimation. At $42.84 per person, a data collection campaign for 29,831 individuals amounts to $1.28 million.

The main challenges to this policy alternative are logistical; it may be difficult to reach all AI/AN youth, especially those in foster care or with unstable housing. Decades of exploitation, violence, displacement, and forced assimilation have rendered indigenous communities deeply distrustful of researchers and U.S. institutions (Pacheco et al., 2013). Data collectors must be mindful of this tension and work very closely with AI/AN community members in order to gather accurate information.

Tongva Land Transfers

The Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy is one of the only organizations in Los Angeles County actively working to return indigenous land to indigenous peoples. 10 board members, most of whom are Tongva, lead the Conservancy and facilitate land transfers with volunteering individuals or foundations (Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy, n.d.).

In October 2022, a private owner transferred an acre of land in Altadena, a city in Los Angeles County directly north of Pasadena, to the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy. This paper recommends modeling land return off of this Altadena transfer, in which the Tongva people acquired the land for $20,000 although it had a $1.4 million value (Purtill, 2022).

Land returns are not simply about regaining geographic territory. A Tongva elder described the Altadena property as “a place where we need to come together, to be ourselves and where we can share ourselves” (Purtill, 2022). According to Cheyenne Bearfoot, a Chiricahua Apache photographer and media creator, such actions have myriad ripple effects:

Although acquiring sovereignty over stolen lands is a key goal, Land Back seeks to heal and reclaim other things that are connected to land reclamation: languages and ceremonies, governmental sovereignty, food, and housing security; equitable access to healthcare and education. (Bearfoot, 2022)

One of the main limitations with this policy alternative, however, is that it is a downstream intervention. Land transfers make an undeniably important and long-lasting impact, but they occur at a very slow rate — one at a time for one tribal group. Such transfers are also dependent on the voluntary actions of individuals and landowning foundations, who may be reluctant to cede their land, wealth, and power. There is no governmental, top-down statewide policy that enforces such land transfers and ensures they will happen at a rate the indigenous peoples of Los Angeles County need and deserve.

Property Tax Shares

Sharing a percentage of property taxes with local tribe governments is part of a larger reparations campaign to account for the historical and ongoing violence and disenfranchisement towards American Indians and Alaska Natives.The basic framework for this recommendation can be found in “‘We Are Still Here’: A Report on Past, Present, and Ongoing Harms Against Local Tribes.” The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, Gabrieleno/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, Gabrielino Tongva Indians of California Tribal Council, San Fernando Band of Mission Indians, and San Manuel Band of Mission Indians wrote this document to mobilize legislators and policymakers of Los Angeles County.

In Los Angeles County, the property tax is 1 percent. As seen in Figure 3, 24 percent is allocated towards unincorporated areas (Auditor-Controller Los Angeles County, 2023). This paper advocates for 0.1 percent to be directed towards local tribal governments out of the 24 percent for unincorporated areas. All in all, this allocation would amount to a minute fraction — 0.001 percent — of Los Angeles County residents’ income. Based on 2022-2023 dollars, this percentage would amount to $191,749 towards AI/AN Los Angeles County tribal governments each year (Auditor-Controller Los Angeles County, 2023).

Such a policy alternative is ideal because it enables AI/AN communities to make their own decisions and allocate the money in the manner they wish — whether it be healing ceremonies, cultural centers, land return initiatives, or anything else. For this same reason, however, this policy alternative is the least politically feasible. Many Los Angeles residents may object to tax dollars spent on communities they deem invisible or unworthy.

Policy Recommendations

In using three criteria — political feasibility, cost, and number of people impacted — this paper recommends implementing the data collection campaign. It has a high political feasibility given that the California State Legislature is relatively progressive and has passed various bills regarding AI/AN communities, youth, and houselessness. The cost, although it may seem high, is a small percentage (0.003 percent) of Los Angeles County’s overall budget of $43 billion (Chief Executive Office, 2023). Moreover, it will impacta greater number of people. Whereas Tongva land transfers may return one or two acres to the Tongva tribe, improved data collection will render tens of thousands of AI/AN youth from multiple tribes visible to the county government and therefore eligible for social and cultural services.

Below is a chart outlining the implementation timeline for such a data collection campaign.

Conclusion

As Executive Director of the Chief Seattle Club Colleen Echohawk said it best: “Prior to 1492, native communities had a 100% success rate in housing” (Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission, 2019). Addressing AI/AN youth houselessness is not about using a deficit-based approach; rather, it is about acknowledging the historical and ongoing harms committed against indigenous peoples and working directly with them to restore their lives and livelihoods. A world with indigenous sovereignty, joy, healing and, of course, housing for all youth, is not only possible — it is within reach.

American Indian Community Council. (2020). About Us. https://www.aiccla.org/about Auditor-Controller Los Angeles County. (2023). Revenue Allocation Summary. https://auditor.lacounty.gov/revenue-allocation-summary/

Bardon, Julie. (2023, April). Indigenous Youth Experiencing Houselessness in Los Angeles. USC Spring Course PPDE 664 Presentation.

Bearfoot, Cheyenne. (2022, April 21). Land Back: The Indigenous Fight to Reclaim Stolen Lands. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/education/535779/land-back-the-indigenous-fight-to-reclaim-stolen -lands

Cai, J. (2020, December 1). The Condition of Native American Students. National School Boards Association. https://www.nsba.org/ASBJ/2020/December/condition-native-american-students

California Coalition for Youth. (2018, September 27). SB 918 Signed into Law. https://calyouth.org/sb-918-signed-into-law/

California Tribal Families Coalition. (2021, September 1). Almost There on AB 873!! https://caltribalfamilies.org/1872-2/

Chief Executive Office. (2023, April 17). LA County’s $43 Billion Recommended Budget is Unveiled. https://ceo.lacounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FINAL-Recommended-Budget-Me dia-Release.pdf

County of Los Angeles. (n.d.). Land Acknowledgement. https://lacounty.gov/government/about-la- county/land-acknowledgment/

Creighton, M. C. & Schoen, E. (2020, January 20). American Indian and Alaska Native Homelessness. Homeless Policy Research Institute. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Native-American-Homeless ness-Briev_V111.pdf

Dickerson, D. L., Brown, R. A., Johnson, C. L., Schweigman, K., & D’Amico, E. J. (2016).

Integrating motivational interviewing and traditional practices to address alcohol and drug use among urban American Indian/alaska native youth. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.023

Digital Public Library of America. (n.d.). History of Survivance: Upper Midwest 19th-Century Native American Narratives. https://dp.la/exhibitions/history-of-survivance/reservation-era

Dobson, A. & Nez, T. (2023, January). “We are Still Here”: A Report on Past, Present, and Ongoing Harms Against Local Tribes. https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/lac/1137966_AREPORTONHARMSCountyofLosAng eles.pdf

Epstein, B. & Lofquist, D. (2021, April 26). U.S. Census Bureau Today Delivers State Population Totals for Congressional Apportionment. United Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/2020-census-data-release.html

First Nations Development Institute. (2023). Investing in Native Youth. https://www.firstnations.org/our-programs/investing-in-native-youth/

Governor’s Office of Tribal Affairs. (2023). Welcome to the Governor’s Office of Tribal Affairs. https://tribalaffairs.ca.gov/

Indian Health Service. (2018, October). Urban Indian Health Program. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/uihp/

James C. Ramos. (2021, April 8). Tribal foster kids to get same educational protections offered other foster children under Ramos bill. https://caltribalfamilies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AB-1055-Ramos-Statement.pdf

Johnson-Jennings, M. D., Reid, M., Jiang, L., Huyser, K. R., Brega, A. G., Steine, J. F., Manson, S. M., Chang, J., Fyfe-Johnson, A. L., Hiratsuka, V., Conway, C., & O’Connell, J. (2023). American Indian alaska native (AIAN) adolescents and obesity: The influence of Social Determinants of health, mental health, and substance use. International Journal of Obesity, 47(4), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-022-01236-7

Jones, Y. & Marinos, N. (2021, June). Innovations Helped with Implementation, but Bureau Can Do More to Realize Future Benefits. Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-478-highlights.pdf

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Native American. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/native-american/

Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Committee. (n.d.). Native American Commission. https://lanaic.lacounty.gov/commission/

Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission. (2019, March). Understanding Native American Homelessness in Los Angeles County: A Progress Report from the Community Forum on Native American Homelessness. https://lanaic.lacounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/LANAIC-Mar-2019-Rpt._2-1.pd f

Los Angeles County Department of Education. (2023). 2021-22 Chronic Absenteeism Rate. https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/DQCensus/AttChrAbsRate.aspx?agglevel=County&cds= 19&year=2021-22

Miller, L. K. (2013). The Secret Treaties with California’s Indians. archives.gov/files/publications/prologue/2013/fall-winter/treaties.pdf

Morton, Matthew H., Raúl Chávez, and Kelly Moore. (2019). Prevalence and Correlates of Homelessness among American Indian and Alaska Native Youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(6), 643–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-019-00571-2

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2023, March 29). Youth Homelessness Overview. https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/youth-homelessness-overview

National Congress of American Indians. (2022, June 6). Research Policy Brief: Native Youth Data.

https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/20220605_N CAI_PRC_Native_Youth_Data_Brief_FINAL.pdf

Nilsson, S. F., Nordentoft, M., & Hjorthøj, C. (2019). Individual-level predictors for becoming homeless and exiting homelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Urban Health, 96(5), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00377-x

Pacheco, C. M., Daley, S. M., Brown, T., Filippi, M., Greiner, K. A., & Daley, C. M. (2013). Moving forward: Breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2152–2159. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301480

Pukuu Cultural Community Services. (2023). Mission & History. https://www.pukuu.org/about-us/about

Purtill, C. (2022, October 11). An acre of land in Altadena has been formally transferred to L.A.’s first people. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/newsletter/2022-10-11/essential-california-land-transf er-tongva-essential-california

Scott, W. D., Clapp, J., Mileviciute, I., & Mousseau, A. (2016). Children’s Depression Inventory: A unidimensional factor structure for American Indian and Alaskan Native Youth. Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000145

Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy. (n.d.). Welcome to Tovaangar. https://tongva.land/ United American Indian Involvement. (2020). Our Mission & Vision. https://uaii.org/about-us/mission-vision/

United States Census Burea. (2023). Selected Population Profile in the United States. https://data.census.gov/table?q=S0201&t=006:01A&g=050XX00US06037

Urban Indian Health Commission. (2007). Invisible Tribes: Urban Indians and Their Health in a Changing World. https://www2.census.gov/cac/nac/meetings/2015-10-13/invisible-tribes.pdf

Walls, M. L., Whitesell, N. R., Barlow, A., & Sarche, M. (2017). Research with American Indian and Alaska native populations: Measurement matters. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 18(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2017.1310640